The story I wrote for the New York Times Magazine on my nephews’ encounter with a mountain lion went through a number of revisions over a number of months before finally launching on December 31, 2024. A lot of context and detail ultimately didn’t make it into the final, published draft, which is normal and necessary for a magazine format with limited space.

However, that fallen away material contributes mightily to a complete understanding of the circumstance, and the politics and policies that led to it. What follows is a more complete accounting, as a resource for others working to retain or restore effective wildlife management in a contentious and often uninformed era. And yes, it’s long.

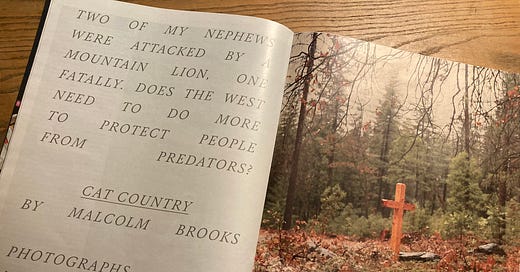

On March 23, 2024, while walking down a Forest Service Road outside Georgetown, California, my nephews Taylen and Wyatt Brooks were confronted and attacked by a mountain lion.

The incident marks the first time in recorded history that one of the big cats willfully confronted face-on and refused to back down from a pair of adult males. And as it happens, this particular pair had grown up fully immersed in the outdoors, in a largely rural part of El Dorado County, hunting deer and turkeys, quail and ducks, and fishing often for bass and trout. On the afternoon of the attack, they’d gone out into the field in pursuit of shed deer antlers, an annual springtime ritual that resulted over the years in an outright mountain of prongs and tines and beams, each specimen meticulously labeled with the date and location of the find. Today, however, would mark the last time this family tradition might simply stand as an innocuous reason to get back out into the woods.

Wyatt, the younger of the two at 18, caught the movement first. He was walking on the uphill side of the road, no more than five minutes out of the car, scanning the slope for the telltale jut of a fallen antler, when he caught a flicker of movement out of the corner of his eye.

“I thought it was a dog at first,” he told me later, but when his head ratcheted around to take in the scene ahead, what came into view was the metaphorical opposite of a canine. A young male lion came up out of the brush on the downhill side, angled toward the boys, and began walking almost casually in their direction. Wyatt described the distance as no more than ten yards, and he’d be the one to judge this accurately—an accomplished archer, he’d taken his first buck with a bow when he was thirteen years old.

Taylen, also on the downhill side of the road and slightly behind his brother, was still scanning the lower slope for antlers, unaware of the lion out ahead. Wyatt said his brother’s name, and both boys immediately followed the standard prescribed procedure for lion encounters, raising their arms above their heads to appear larger, shouting and yelling and backing slowly away.

The lion did not respond in the predicted fashion but kept right on walking, directly toward them, eyes locked and pads gaining ground as they continued their backward retreat. When the distance had closed to a matter of feet, Wyatt unslung his backpack and hurled it, the pack glancing off one side of the cat’s face. He said it never paused in its approach, never seemed to react at all other than to blink a time or two upon impact.

Then Wyatt tripped on a stick in the roadway and went over backwards as the cat instantly pounced, coming down on him even while he hit the ground. One pair of fangs sank into his left cheek, below the orbit of his eye socket and along his jawline, the other into his upper lip and right nostril, flaying his face open in four separate, slicing penetrations.

Later, in the hospital, he told my brother that the cat appeared “huge,” which of course it must have, in that harrowing moment. Fortunately it was in fact half-grown, at around ninety pounds—huge enough to present an entirely deadly threat, but not so huge as to prevent my adrenaline-driven nephew from flipping it on its back and ripping the lion’s head away from his own, both hands clutching the lion’s throat. At that point the cat went fully berserk, grabbing with its front claws and raking Wyatt’s torso with its rear, in the way all felines everywhere use their powerful haunches to eviscerate prey.

Already gushing blood from his face, Wyatt had no choice but to let go and spin away. The instant he did—and all of what I’ve just described took place in mere seconds— the cat spun up as well, and went for his brother.

*

Although lion attacks on humans in general are statistically rare, they’re less rare in contemporary California than they once were. To dissect the underlying reasons, it’s helpful to understand the relationship between man and mountain lion in the Golden State over the past century.

Prior to the modern era, the only known human deaths from this sort of encounter in 20th-century California occurred in 1909, when a rabid lion attacked two people. Both victims survived the initial encounter, but later succumbed to rabies themselves. No other attacks against humans were documented at all in the state for most of the next eight decades.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1907, California offered a bounty for mountain lions, with up to four state-paid professional lion hunters employed full-time as part of the effort. This was an era in which apex predators in general were largely viewed as diabolical, even Satanic marauders, with no ecological benefit or intrinsic value. The eradication of such species was considered a necessary if not noble goal.

While the state’s native grizzly bear and gray wolf populations were totally extirpated by this same logic in the mid-1920s, the mountain lion proved much more resilient. The bounty system continued until 1963, when the species was simply classified as vermin. Although a cash reward could no longer be had, no regulation or management strategy limited the number that could legally be killed. And unlike during the bounty era, no record was kept regarding how many actually were.

By the end of the decade, a growing number of the state’s citizens began to worry that the largely unseen lions might be headed for extinction. Interestingly, some of the concern came from Rod-and-Gun-club types, particularly those who used hound dogs to pursue both lions and black bears—in that particular realm of hunting culture, most of the excitement involved the chase itself, and more often than not the treed quarry would be released to run another day. But with no real notion of how many lions actually existed to carry the pursuit forward, an effort to re-classify the species as a game animal succeeded in 1969, which for the first time put the lion population under the management of the California Department of Fish and Game.

This didn’t of course answer the question of exactly how many lions roamed the state in the first place—that was a conundrum that required long-term, legitimate biological study, and the science of large-predator conservation was only barely in its infancy. However, traditional tracking hounds remained crucial even to that endeavor, since no other orchestrated method for locating and encountering lions in the wild actually exists.

As part and parcel of the early effort to fold the California mountain lion into the bigger picture of comprehensive wildlife management, Governor Ronald Reagan signed a four-year kill moratorium into law in 1971. Pursuit permits would still be issued to allow hound-handlers to run and tree the big cats, not simply for sporting and dog-training purposes, but also as a form of data-collection in the incipient effort to establish a population count. Meanwhile, several state biologists began limited studies in independent areas, making use not only of hound tracking but also newfangled radio telemetry collars, a method that would increasingly become standard equipment as the technology continued to improve, and knowledge of lion behavioral patterns and life cycles began to accumulate.

By the middle of the decade, several tentative population estimates appeared, with the lowest at approximately 2,400 animals statewide—but with the scientific methodologies still a work in progress, and the animal itself such an evasive mystery, even the researchers acknowledged that these were back-of-the-napkin guesstimates. The kill moratorium was extended, and extended again, while more data was collected. Meanwhile, the state’s private hound handlers continued to run and tree and release mountain lions with annual pursuit permits.

It’s worth noting that lion-confirmed livestock depredations in the state during most of the moratorium era—ultimately a 14-year span—remained relatively low, hovering in the single- or double-digits for the entire state until 1985, when it jumped to nearly 150. 1986 showed a similar number of livestock kills, as well as the first attacks on humans in nearly eighty years, in which a pair of kids aged 5 and 6 were attacked seven months apart, in the same wilderness park in Orange County.

These statistics, along with an updated population estimate of 4,800 lions, likely played into the decision to end the hunting moratorium, and return management to the Department of Fish and Game. (If such a population number seems low to the casual observer, it’s actually fairly normal for this particular species. Montana, for example, rigidly monitors its own lion population and currently puts the number at around 6,000 animals—and further calculates this figure to be within 25% of the pre-European contact population.)

What played out over the next four years would in retrospect achieve the opposite of the state’s attempt to manage lions within the framework of comprehensive wildlife conservation, putting a rolling snowball of increasingly negative encounters into motion that, from my family’s perspective, eventually barreled right over my nephews, nearly four decades down the slope.

*

“Taylen didn’t do anything wrong,” Wyatt told us later. “It just happened so fast, there wasn’t anything he could do at all…”

By the time the lion started in on his torso and forced him to retreat, well under a minute had transpired from the moment the cat first presented itself. Now, half-blinded by his own flowing blood but feeling nothing for pain, he nonetheless watched the cat come up onto those same back haunches and slap down with its front paws, pushing his brother backwards into the dirt and duff on the roadway. From Wyatt’s perspective, Taylen’s face disappeared behind the back of the cat’s head, as the jaws that had just clamped on his own face locked now around his brother’s throat and neck.

“It was like watching something in a dream,” he said, “only I knew it wasn’t a dream, and I had to wake up…”

He saw that Taylen’s hands were up underneath the lion’s head and neck, as though trying to protect his throat or maybe grab the lion’s throat the way Wyatt himself had seconds earlier, and he snapped out of whatever fugue-like state his mind had entered and jumped onto the back of the cat.

“I grabbed it by the neck again and tried to pull it off, but I couldn’t. No matter how hard I tried, it just wouldn’t let go.” Eventually, he said, he realized Taylen’s hands had fallen away from under the lion’s head, his arms completely limp, and somewhere in his own frenzied panic he realized that the situation could only get worse. He let go of the animal himself.

Even as he backed away, two thoughts flashed in his mind—call for help, and go for the car, on the chance he could drive it around the gate and somehow use it to haze the animal away. He scrabbled around for his phone, found it was no longer in his pocket. Spotted it in the dirt and went for it. By the time he picked it up, he had a half-delirious sense that the lion was now dragging Taylen over the downward edge of the road, back into the brush that the big cat had first emerged from maybe one minute earlier.

*

Growing up in El Dorado County in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, my brother Aaron and I had interests and lives very similar to those of Taylen and Wyatt.

We were both drawn to the outdoors from a very young age, and earning a hunting license represented a rite of passage into the world of hands-on, ancient interaction with the wild environment around us. We hunted deer and quail and doves, and learned how to dress and prepare the yield of those pursuits. Once wild turkeys began to proliferate in the Sierra foothills, we welcomed the opportunity to expand what had been an autumn endeavor into the glorious green of springtime, the traditional season for gobbler hunting.

One thing that differed drastically, however, was the odds of an encounter with a mountain lion. Everybody knew the big cats were around, all the time, but daytime sightings were rare enough to remain actually newsworthy. We would hear a lion scream in the dusk from time to time, a bloodcurdling sound indeed, down in the plunge of the canyon behind our house. Occasionally somebody we knew would glimpse one in the headlights on some winding mountain road, but we literally never went out into the deer or turkey woods with any thought that we might be in any danger from a cougar ourselves, even while decked out in head-to-toe camo, mimicking the sound of a hen turkey with a mouth-call.

Our own formative years overlapped with the end of the kill moratorium era in 1986, which almost immediately led to a shift in the broader politics around the state’s mountain lion population. It seems that so long as the moratorium remained in effect, the animal advocacy and activist communities were satisfied to leave well enough alone, even to the point of ignoring or perhaps just overlooking the ongoing legal permitting for hound pursuit on a catch-and-release basis, or what’s known in that world as “tree-and-free.”

Once the state returned management to what was then known as the Department of Fish and Game, organizations such as the Mountain Lion Preservation Foundation (now the Mountain Lion Foundation) and the Humane Society of the United States went on a different sort of warpath, filing lawsuits to pre-empt lethal-take hunting as a conservation tool and lobbying to have the mountain lion protected uniformly as a threatened species.

Although the scientific study of the cats and the data collected over the moratorium years had progressed enough to produce a total statewide population estimate of 4,800 lions, the number preferred and promoted by the preservationist lobby remained the mid-1970s conjectural estimate of 2,400.

A 1986 paper presented by two agricultural extension specialists from UC Davis noted both figures, but also honestly acknowledged that, “Biologists do not know how many lions are in California,” before nonetheless concluding that, while more information would be welcome, enough data did exist even then “to allow management of the mountain lion according to biological principles.” As agricultural experts, the authors probably had in mind the considerable uptick in livestock depredations, and the attendant uptick in lions euthanized as a result (an exception written into the original moratorium decree). The logic being that a return to limited sport hunting would in turn at least partially supplant the increasing depredation tally, with fewer lost livestock in the process, while at the same time contributing to rather than depleting the state’s wildlife funding.

In retrospect, perhaps the paper’s most prescient observation occurred in its conclusion: “We should also recognize that management of the mountain lion affects many individuals and interest groups and is therefore a political decision.”

This statement would become a harbinger of a very-near future, in which ideology would ultimately trump biology, with increasing repercussions. Right up to that sobering day this past spring, when Taylen and Wyatt confronted an unchallenged apex predator that simply did not follow the commonly accepted script for human encounters.

*

By the time he retrieved his phone from the dirt at the site of that initial, violent contact, Wyatt was gushing blood from the gaping wounds to his face. With the body of his brother even then being dragged off the roadway by the neck, he tried to dial 911 but couldn’t at first, because he’d already bled so heavily on his hands that the slick glass surface of the phone screen wouldn’t respond to the equally slick swipe of his fingers.

Imagine the desperation—half-stumbling, half-running back toward the car in a fusion state of adrenaline and shock, bleeding heavily out of multiple gashes to the face, all the while trying to get this damned piece of useless tech to work. Which he finally did, about the time he got to the car.

911 dispatch had no idea what to tell him, other than to stay in the car until help arrived. He peeled out of his shirt, and used it to absorb some of the blood that continued to flow from the wounds in his face.

Still, Taylen. With no certain notion of the fate or condition of his brother, Wyatt stayed on the line with the dispatcher, but fired up the car and managed to drive over the brush and rocks off-road to get around the locked Forest Service gate, then back up to the scene of the attack, marked now only by the backpack he’d flung at the cat moments earlier.

Both the lion and his brother were gone.

*

By 1988, the California Fish and Game Commission still hadn’t been able to reinstate a regulated hunting season for the newly re-classified mountain lion. Its members had tried, but were blocked twice by lawsuits filed by activist organizations, with additional support from more generalized environmental advocacy groups like the Sierra Club and the Planning and Conservation League.

Meanwhile, when a bill in the California assembly that would permanently ban lion hunting died on the vine, its proponents resorted to another tactic, one that in retrospect seems tailor-made for a state with a gargantuan, otherwise unaffected urban populace: the popular ballot measure. And that’s when the PR war truly got hot.

A full-page ad taken out by the Mountain Lion Preservation Foundation described hound pursuit—the standard method of take for large carnivores going back centuries if not millennia—in garish if wildly inaccurate terms, describing the outcome of a lethal hunt as “blowing the animal to bloody lint.”

A Los Angeles Times story on the grassroots ballot effort from May, 1990, described a “volunteer force blitzing shopping malls all over the state,” with petitions bearing “a blown-up likeness of a mountain lion.”

The same story featured a reaction from a division chief of the Department of Fish and Game, who stated, “This is a sensationalized, emotional issue,” and characterized the signature gathering sessions as “typically a couple of individuals who have no technical background or knowledge . . . they have a big picture of a domesticated lion, and they say, ‘Please sign here if you want to save the lions. They’re killing ‘em.’”

Meanwhile, the previously mentioned academic paper presented by the UC Davis extension specialists noted that, during arguments over the issue, “lions often were referred to as ‘threatened,’ ‘endangered,’ or ‘rare.’”

Most if not all veteran wildlife biologists at both the state and university level disagreed with this conjecture, often vehemently, and even the better-informed anti-hunting advocates were at times forced to concur. The Times story cited above also featured a statement from the director of the Planning and Conservation League: “The mountain lion is not an endangered species. It is not threatened by extinction from hunting. We would never argue that.”

Except many others on that side of the aisle were arguing exactly that, however erroneously or disingenuously. So while the activist organizations may have lacked biological basis for their position, they were nonetheless first-chair masters at sawing away on the heartstrings. And it worked—with the petitions finally tallied, the shopping mall volunteers had gathered nearly 700,000 signatures, practically double what the law required to put the measure on the ballot.

Dick Weaver was one of those steely-eyed, old-school biologists who expressed alarm at the very notion of taking wildlife management out of the hands of scientists and into the whim of the public. A forty-year-veteran of the California Department of Fish and Game, Weaver had over the course of his long, field-based career done pioneering work with all manner of wildlife, including the state’s precarious population of bighorn sheep. He was also the first state biologist to utilize radio collars to get a read on the actual lion population, clear back in the early days of the kill moratorium.

“Losing mountain lion hunting doesn’t make a hell of a lot of difference in how many mountain lions are going to be out there at any given time, because the quotas are so small,” he said at the time. “But what I worry about is losing an opportunity to hunt by referendum . . . I’ve always said that biology wouldn’t have a damn thing to do with the status of mountain lions. Emotion was going to rule.”

When Proposition 117 passed in the next general election, Weaver may not have realized that the sweeping measure would not only permanently ban lethal-take hunting of the species, but also by implication the longstanding, non-lethal exercise of tree-and-free pursuit by hound handlers. In retrospect, relative to the behavioral tendencies of lions in proximity to humans, that’s the provision that may have truly opened Pandora’s Box.

*

Once Wyatt determined that both Taylen and the lion were no longer on the road, the dispatcher on the phone instructed him to drive back down to the gate and wait for help to arrive. About fifteen minutes later a pair of deputies roared up, followed shortly by an ambulance. While the medics went to work on Wyatt, the deputies armed themselves with rifles and went in search of his brother.

They found the backpack, the signs of the struggle, and—difficult as this is to write—the drag trail, through the brush down off the side of the road. It didn’t take some genius tracker with supernatural abilities to follow the path, nothing like the poetic folklore of tracing the route of a snake across a flat rock in the desert. Instead they walked up on the cat within a hundred yards, still crouched over Taylen’s inert form.

They could not of course shoot directly at the animal, for fear of accidentally hitting the victim they were still against all odds attempting to rescue. They did touch off their guns into the ground, in an effort to haze the animal away with the noise. It only partially worked—the cat did abandon its prey, but not to retreat, exactly. Instead it rushed the deputies, who again tried to haze it away with gunfire. It flinched away at first, only to wheel back and attempt another charge. Gunfire again, and then again after another rinse-repeat, before finally the lion vanished into the brush.

*

Proposition 117, otherwise known as the California Wildlife Protection Act, passed by popular vote on June 5, 1990, designating the mountain lion a “specially protected mammal” a full 18 years after it had last actually been hunted in the state at all. (As a critical aside, a paper published by the department’s wildlife lab flatly stated that this “unique status was a political designation, and not based on biological information regarding population abundance or trend.”)

In addition to banning sport hunting in perpetuity, the language of the statute went considerably farther, by explicitly barring the Department of Fish and Game from adopting “any regulation that conflicts with or supersedes” the statute’s general spirit of preferential protection. Although nothing in the measure specifically referred to non-lethal hound pursuit, the general prohibition on any sort of unauthorized “take” was construed to encompass this. For the first time in California history, willfully turning a hound dog onto a lion’s trail became a criminal offense.

At the time, nobody really understood the overarching impact of competitive pressure on lion behavior, because no human society had ever lived in proximity to a virtually uncontested mountain lion population. In natural history terms, outside of humans, the lion’s only meaningful rivals are grizzly bears and wolves, neither of which can climb trees but both of which can take a lion’s prey, or alternatively, kill it for food—hence the lion’s evolved mechanism of escape and evasion, straight up into the overhead branches and limbs.

This same tendency likely became exploited by humans clear back in the Paleolithic, when ancient hunter-gatherers with companion canines first populated the Americas. It continued into the era of the modern tribes, as indicated by an 1834 entry in fur trapper Osborne Russell’s personal journal. He’s referencing an encounter in what we know today as the Lamar Valley, in the northern region of Yellowstone National Park:

"Here we found a few Snake Indians comprising 6 men 7 women and 8 or 10 children...Their personal property consisted of one old butcher Knife nearly worn to the back two old shattered fusees which had long since become useless for want of ammunition a Small Stone pot and about 30 dogs on which they carried their skins, clothing, provisions etc on their hunting excursions. They were well armed with bows and arrows pointed with obsidian...We obtained a large number of Elk Deer and Sheep skins from them of the finest quality and three large neatly dressed Panther Skins...”

Thirty dogs would have equated to a lot of extra mouths to feed, so the canines were obviously proving themselves useful. And to this day, trained dogs represent the only realistic method for human hunters to take a mountain lion. By the time Europeans arrived on the scene with their own purpose-bred hunting dogs, the continent’s original inhabitants had already perfected the exercise, probably thousands of years earlier.

As noted, both grizzlies and wolves had been extirpated from California in the 1920s, which left only hound-assisted humans as the singular, top-of-the-food-chain competitor. Now, with this final external pressure almost totally eliminated (under livestock depredation and scientific study exceptions, limited hound pursuit could still be narrowly applied), those of us in the rural foothill communities began to see changes in lion behavior. Livestock and pet depredations continued to climb—even our longtime neighbor, a multi-generation rancher, lost a couple of sheep in his pasture, a first for him.

Somewhat more strikingly, within two years people all over the county were actually seeing mountain lions, not only in the high beams at night but in broad daylight, with increasing regularity. Crossing the road, loafing in the shade at the edge of a pasture, skirting a campground. My brother actually had one run into the side of his pickup one afternoon, deflect away, and depart apparently unscathed into the oaks and manzanitas along the road.

Lion encounters ratcheted up elsewhere in the state as well, and not only with depredations and firsthand sightings. In 1992, a 9-year-old boy on a bike ride with his family near Santa Barbara was attacked and badly mauled by a young male lion, resulting in more than fifty puncture wounds and 600 stitches.

In 1993, Cuyamaca Rancho State Park near San Diego was closed for several weeks after a number of visitors had too-close-for-comfort encounters with an aggressive lion, including a pair of women on horseback. Park rangers tried unsuccessfully to track the lion during the closure. The first weekend after reopening, a lion believed at the time to be the same offender walked into a crowded campground and bit a 10-year-old girl before being driven off by the family dog, which was also mauled. Responding park rangers shot and killed the cat not far from the campground.

Then, in April, 1994, right in our own backyard in El Dorado County, a 40-year-old woman named Barbara Schoener disappeared while jogging in a public recreation area near Cool, California. Her partially-consumed body was discovered the next day, neck bitten and skull crushed, in a mound of debris indicative of a mountain lion cache. Six days later, after intensive tracking efforts, a lion was treed by hounds and euthanized not far from the scene of the attack.

Barbara Schoener became the first lion fatality in California since 1909. Incidentally, the site of her demise was not 10 miles from where Taylen and Wyatt were attacked nearly three decades later, short exactly one month to the day.

*

I graduated from El Dorado High School with John Chandler in 1989, and though we had mutual friends, we didn’t know each other well. Just running in different circles, never knowing that fate would permanently connect us, thirty-five years down the road.

Like myself and Aaron and then Taylen and Wyatt, John grew up hunting and fishing in the heart of Gold Rush Country, and eventually converted that passion for the outdoors into a career as El Dorado County’s Wildlife Specialist, or what’s known in the common vernacular as the county trapper. Any time an agricultural producer or horse owner or home gardener has a persistent issue with dangerous or destructive animals—skunks denning under a shed, raccoons raiding a chicken coop, bears breaking trees in a commercial orchard or gorging on Zinfandels in a vineyard— John can assist, either with advice or, if necessary, direct intervention. Over the past few years, a growing percentage of calls have involved mountain lions.

“I was actually up at West Bowl skiing when the first call came through at 1:30,” he told me. It wasn’t a typical weekend contact from a dispatcher or general citizen—this was a direct call from Jeff Leikauf, the El Dorado County Sheriff, telling him that a mountain lion attack had just been reported, that he didn’t have all the details but needed John to get down the hill.

Any lion attack on any human would put any first-responder into a state of adrenalized urgency. But as Chandler reached his car at the bottom of the ski hill, another call came through that put his heart rate into overdrive: confirmed fatality. The lion itself remained unaccounted for.

He drove down the mountain at breakneck speed, got his trio of hounds crated and sped on, arriving at the gated road just over two hours after he’d first been summoned from the ski slopes. Wyatt had already been ambulanced to the hospital. The coroner’s van was just leaving with Taylen.

“I’m glad I didn’t know who the victims were at the time, and I’m glad I didn’t have to see Taylen,” John told me later. Even though he and I only knew each other peripherally in school, and I’ve now lived in Montana for close to three decades, he’d gotten to know my brother well in the intervening years. But all he had in the moment were the basic details—two random young guys, out looking for fallen antlers. It struck a chord, just not in the moment a personal one.

By now a storm front had blown in, the late afternoon sky dumping rain. Deputies and a pair of state game wardens led him to the recovery site down off the roadway, where Taylen’s crushed ball cap still remained. Chandler turned his Walkers loose, down into thicker timber. Within minutes, the howling of the dogs told him they’d run a lion up a tree.

*

Eight months after Barbara Schoener became the first lion fatality in California in eighty-five years, another woman fell victim to the same fate—in Cuyamaca Rancho State Park, the same location that had already witnessed the earlier attack on the 10-year-old camper. In the interim, three other lions had also been euthanized in Cuyamaca, after showing aggressive behavior toward humans.

“The lions are behaving in a way we historically did not think they would,” a park ranger told the Los Angeles Times.

The same report also noted that, “In the past, zoologists have surmised that only a diseased, rabid or crippled mountain lion attacks people and that a healthy lion flees at the sight of a human. But Cuyamaca mountain lions that have menaced or attacked visitors have been healthy.” Additionally, the Times stated, “Mountain lion sightings have become increasingly common in California.”

Two other non-fatal attacks also occurred in 1994 and 1995—one involving a mountain biker in the San Gabriel Mountains outside Los Angeles, and the other against a pair of adults in Mendocino County. Alongside steadily increasing livestock and pet attacks, the Department of Fish and Game began an equally steady issuance of lethal depredation permits, under the provisions for such in Proposition 117.

Between 1994 and 2019, well over one hundred lions on average were legally removed annually—a far higher number than occurred during all but the last couple of hunting moratorium years (1972-1986), when tree-and-free pursuit licenses were issued. And at a success rate, it must be noted, of less than fifty percent, when levied against the total number of depredation permits actually issued in the post-117 era. Which means that at least some number of lions that were not successfully taken via depredation permitting nevertheless experienced some degree of pursuit pressure, and at least some of that would have come from tracking hounds.

This is important for a couple of reasons, but we’ll begin chronologically. After the Mendocino County attack in 1995, and the start of increased depredation permitting, things cooled off for a spell. No other human attacks were reported in the state until 2004, when a mountain biker was killed in Orange County, followed by a nonfatal attack in the same region that same month, and another nonfatal attack in Tulare County later that year.

The next fifteen years saw four more nonfatal attacks in disparate regions around the state. Which brings us to 2020, when a statewide policy change affecting depredation permitting went into effect that, in retrospect, changed the equation entirely.

By this point, the Department of Fish and Game had a new name reflecting a shift in the perceived purpose of the agency, and probably changing cultural attitudes as well. Now known as the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the division reacted to both activist pressure and a certain amount of public dismay at the circumstances of a handful of radio collared lions living in proximity to densely populated urban centers.

In a way these cats had become “celebrity lions,” written about in magazines and featured in human interest tv news stories. When a depredation permit was issued following alpaca kills near Malibu in 2016, resulting negative publicity and pressure (including, according to the Deseret News, actual death threats) dissuaded the landowner from utilizing it.

The Mountain Lion Foundation offered to build lion-proof pens to shield the property’s remaining livestock, with the foundation’s then-director, Lynn Cullen, telling the New York Times, “Everywhere we study them in California, they are in serious danger. The future looks grim for them unless we find a way to better resolve the conflicts that can arise between them and domestic animals.”

This was a notable statement in a couple of ways, not least the fact that the foundation does not conduct or fund independent research in the first place. More to the point, virtually nobody involved in actual, boots-on-the-ground analysis was making such a claim—including scientists who themselves shared a more preservationist ethic. Mark Elbroch is a lead biologist for Pantherea, a separate, global wild feline advocacy group. He’s also the author of The Cougar Conundrum, highlighting the role of the mountain lion as a key player in broader ecosystems, and a book highly touted by the Mountain Lion Foundation itself. But as he stated that same year, “In most of the west, mountain lions are stable … In California, where they are protected, the population has clearly grown in recent years.”

Regardless of the inconsistent narrative, the visibility around the situation in Malibu prompted the state to deviate from the original depredation mandates required under 117 by implementing a “3-strikes” policy in certain urban interface zones, wherein a problem lion would be given multiple chances to cease and desist before a final, lethal solution was attempted.

The first Malibu lion to cross the threshold occurred in January, 2020, when a male outfitted with a radio-collar by the National Park Service reached a tally of twelve domestic animals in multiple attacks. A depredation permit resulted in a dead lion. It also resulted in a lot of a publicity and a new wave of activist outcry, with some calling for Governor Gavin Newsom to ban depredation permitting altogether, despite the unassailable provisions for such in Prop. 117.

Ironically, Newsom’s father had been a principal architect of 117 in the first place, and a founding member of the Mountain Lion Foundation. William Newsom was a California state appellate court judge, and an administrator of the Getty oil fortune. He was also, perhaps somewhat paradoxically, a staunch environmentalist. A Sacramento Bee headline from February, 2020 declared that Gov. Newsom’s dad helped protect California mountain lions. Now his son faces the fallout.

The accompanying article noted that the proposition’s hard and fast livestock depredation provisions “secured protections for ranchers to shoot mountain lions that kill or maim their livestock,” a guarantee that had helped to get the bill’s otherwise near-total protections first enshrined into law. Thirty years on, those exceptions had become “a thorn in the son’s paw.”

“ ‘We can’t do it,’ Newsom said of requests he’s received to ban the lethal cougar permits altogether. ‘Candidly, that’s frustrating to me.’ ”

However, in truly slippery—and slippery slope—fashion, the Department of Fish and Wildlife cooked up a workaround, by extending the “multiple-strikes” policy statewide the following June, with almost instantly observable fallout in the other direction.

In 2020, the number of lions removed—i.e., killed—on depredation permits statewide dropped by about half from the previous norm, which makes sense given that the new policy came in with the year already half-over.

The following year, just sixteen lethal permits were issued, with a mere three depredating cats actually removed. In 2022, eighteen lethal permits resulted in a total of ten lions removed.

More to the point, attacks on humans quickly began to escalate. Between 1995 and 2019, eight people were attacked by lions statewide, including the fatal strike on the Orange County mountain biker in 2004. Between 2020 and 2022, six more attacks occurred, all non-fatal and all but one targeting kids under the age of eight.

For the purposes of our immediate story, 2023 was a bit of a watershed year for El Dorado County. Lion sightings and livestock depredations had become alarmingly commonplace, as reflected by the number of lethal permits issued relative to the remainder of the state. Out of 31 permits approved in all of California, a full dozen were in my home county. Meanwhile, in San Mateo County three hours west, a five-year-old boy survived an attack on a hiking trail early that same year.

This brought the state’s tally of attacks on humans up to seven in a three-year period, just one shy of the total for the previous twenty-four. A little more than a year later, the incident with Taylen and Wyatt would push the number above even that. It would also include the first fatality in two full decades.

*

John Chandler’s working hounds had indeed pressured the lion into the upper reaches of a fir tree, less than a hundred yards from where Taylen’s body was recovered. After consultation with the accompanying wardens, he took the animal with a single, surgical shot.

The outpouring of community support for Wyatt and the rest of the family was immediate, and intense. In keeping with the outsized number of depredation permits issued locally, many residents had already been dreading such a circumstance anyway. Livestock and pet losses had been escalating for years, and sightings even around municipal housing zones were frequent enough that people were afraid to let their kids ride their bikes, afraid to go for a jog, afraid to walk their dogs on established trails.

The heightened sense of concern got another boost, ten days after the attack. John Chandler was called out to a livestock kill just outside the city limits of Placerville. He wound up tracking the offending lion to a nearby paved walking path, practically within rock-chucking distance of an elementary school playground, a senior living center, and the Walmart parking lot.

After his dogs got it into a tree, several hours of deliberation between Fish and Wildlife and local law enforcement went on about how to proceed, before the lion closed the question for them. It came back to ground of its own volition and went after the dogs, at which point Chandler had no choice but to shoot it as well.

As if that wasn’t unnerving enough for an already on-edge general populace, John was called out again to the same property, one month and one day later, after a second lion came into the yard and killed the landowner’s dog. John’s hounds treed this cat less than a hundred yards from the one that previously charged his own dogs. Both were big, healthy, mature males at the upper end of the size spectrum at 165 and 175 pounds, nearly double the size of the cat that attacked Taylen and Wyatt.

Lions attacking a pair of adult men, lions jumping into a fenced yard to snatch the family dog in the middle of the day. Lions coming down out of a tree to engage with the hounds that chased it there in the first place. Lions hazed away by gunfire, then turning around and charging back for more.

“Lions don’t do that,” John told me. “They don’t come back once they’re hazed off. But this is the weirdest year.” He pauses a minute, then goes on. “Over twenty-five years, I’ve had calls for maybe a couple of horses that got attacked. This year, we’re already up to five.”

I already knew that escalating mountain lion predation on Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep had ominously turned back the survival clock on that particular, federally protected species, and I asked him now about the health of the deer herd locally. As it turned out, John’s also an accomplished horseman who frequently takes his family riding in the mountain high country.

“It’s rare to see a buck up high but I probably see a bear every other time I ride,” he told me, California’s booming black bear numbers representing another stressor on the deer herd, particularly with fawns. “The deer population sucks in the mountains, but thriving in the subdivisions.”

“Let me guess,” I asked him. “The deer fled the lions and bears into the suburbs, and now the lions are following them.”

He had a one-word answer. “Exactly.”

I asked him what he thought should be done at this point, and he was just as succinct. “Go back to the original policy for depredation permits. If people take reasonable precautions and a lion kills, they [CDFW] write a permit. It worked better than this does.”

*

There are many explanations offered for the rise in lion sightings and negative encounters—people on the affected side of the issue tend to focus on the exponential math of increasing lion numbers after a full half-century without hunting, while those on the protectionist side cite everything from habitat loss from development and wildfires to the increasing presence of home security cameras. Maybe it’s all true, to some extent, depending on which region of the state you’re talking about.

But it seems as well that lion behavior has changed as human policy has changed, and as the passage of time has reduced and then reduced again the levels of external pressure on a king-of-the-hill predator.

So what can be done, at this stage of the game? As it happens, California isn’t the only Western state with similar issues. Oregon and Washington followed the ballot-box pathway blazed by the Golden State, not with total hunting bans, but by forbidding hound pursuit as a method of take.

After a similar escalation of pet and livestock depredations, and in Washington, the first human fatality in nearly a century, a wildlife biologist named Bart George saw the consistent pattern—the absence of tracking hounds relative to increasingly bold lion behavior. So he designed a long-term study testing the effects of tree-and-free pursuit on a lion population, which was then sponsored by his employer, the Kalispel Tribe of Indians, a federally recognized sovereign nation with a reservation north of Spokane.

Part of what motivated both George and the tribe was the snowballing depredation problem—and more specifically, he told me, “to keep depredation removals from being thrown in the garbage like a piece of trash.”

The study lasted four years and utilized not only trained hounds and state-of-the-art GPS tracking collars, but a constant barrage of voice recordings as a source of human-associated stimulus. George would pinpoint collared lions by satellite coordinates, often in gulp-inducing proximity to walking trails and residential housing. He would then approach on foot, to the steady chatter of a podcast or talk radio program.

A control group of lions experienced only the human stimulus, with no canine component. These animals quickly acclimated to the presence of people, generally declining to leave their hiding places even as George with his blasting speakers came within a matter of yards.

With the test group, however, the approach of a human was then coupled with the release of tracking hounds, which of course pinpoint their quarry not with the modern miracle of tech but with the primordial miracle of their noses. Once the commotion of the hounds compelled the cat to abandon its bed, the dogs would then pursue, until the lion either went up a tree or gave the dogs the slip.

Regardless of the outcome, a pattern emerged—the more times any individual lion experienced hound pressure, the more quickly it abandoned its bed in reaction to human presence alone, before the hounds were ever loosed.

Ironically, or maybe prophetically, the study concluded the same month Taylen and Wyatt were attacked, two states away. The results have now been formally published, and the practical outcome leaves little to the imagination—lions can in fact be conditioned, by reinforcing their own evolutionary hardwiring to evade other apex competitors. Which is no doubt why livestock depredations were minimized and attacks on humans virtually nonexistent during the moratorium era in California, when pursuit-only permits were still allowed.

Wildlife managers throughout mountain lion country have taken a keen interest in Bart George’s work. As Jim Williams, a career biologist for the state of Montana and author of the book Path of the Puma, told me, “Most wildlife biologists, including myself, tend to rely on the notion that cats are so hard wired genetically that behavior modification is out of the question. Bart and the Tribe are doing groundbreaking work, and it may provide a much-needed management tool.”

For that matter, even the Mountain Lion Foundation has been following the study. Brent Lyles, the current director, emphasized that a large part of the foundation’s efforts these days involves promoting coexistence between humans and mountain lions—as the organization’s mission statement reads, Our vision requires humans to respect and trust, not fear, lions in proximity. A large part of that ambition involves learning more about how human-lion conflict might be minimized in the first place.

“Bart is asking the right questions,” Lyles said, while acknowledging that the mountain lion historically has been so difficult to study that there are still plenty of unknowns—and what’s really needed across the board is more formal study not only into lion behavior, but the possibility of influencing lion behavior, as part and parcel of the goal of coexistence.

“From a hard-core science point of view, it’s hard to do research on non-lethal deterrents,” he added, referring to the standard recommendations for discouraging lions away from livestock. “There are devices you can use like blinking lights, flags, even just leaving a radio playing. There’s a ton of anecdotal evidence that certain things work in certain situations.”

When I asked him if he would consider endorsing preemptive, tree-and-free hound pressure as a viable method, as Bart George and the Kalispel Tribe were trying to demonstrate, he answered perhaps carefully, but not negatively. “I’d consider anything that’s an effective strategy for peaceful coexistence, and hazing is one of those areas,” he said, stating again that he hoped more research might lead to a clearer path forward.

As it happens, a second recent study echoes George’s findings. Researchers contrasted lion behavior in the adjacent states of California and Nevada, the latter of which allows both nonlethal hound pursuit and a legal, limited harvest season. The results, published in the August, 2024 edition of Ecology and Evolution, indicate that the Nevada lions are considerably more inclined to avoid human habitation areas altogether.

Still more recently, in the wake of human encounters culminating in the attack on my nephews, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has acknowledged the necessity of adaptive management. Circumstances in different regions by definition require different strategies. In early 2025, the department announced a partnership with researchers from Utah State to test the efficacy of various hazing strategies—including the use of hounds. The project will focus on the current hot zone of El Dorado County, plus the adjacent Sierra foothills counties. So for the first time in decades, tree-and-free is not only part of the discussion in California, but will actually be studied as a management tool.

*

Finally, Wyatt.

The ambulance rushed him to the hospital in Placerville, where the doctors determined that his injuries required more than they could best provide. A second ambulance rushed him down out of the foothills, to the UC Davis Medical Center.

By this point, nobody had actually confirmed for him the fate of Taylen, and though he kept asking, nobody would. Until my brother arrived.

Aaron and his wife Stacy had been up the mountain at South Lake Tahoe for a birthday celebration when the attack happened, and Taylen’s whereabouts were initially reported as still-unknown. He and Stacy then crawled down US 50 in a blinding snowstorm, with no cell service. They only learned the full story themselves when they arrived at UC Davis.

The two of them and the boys’ mother, Amanda Welsh, went in together as Wyatt was being prepped for reconstructive surgery. Even then, Wyatt’s only concern was knowing what had become of Taylen. My brother had to tell my nephew that his own brother didn’t make it.

Wyatt put his swollen, damaged head back against the pillow, looked up at that hospital ceiling, and said one word. Seriously?

Some genius of a plastic surgeon worked on Wyatt literally through the night, not in the actual surgery center because no room was available. Instead he had his kit brought down to the ICU, and performed an eight-hour miracle.

I saw photographs of Wyatt in the immediate aftermath and they did not suggest the way he appeared when I actually saw him in person, exactly one week later. Yes, the long pair of scimitar-like scars along his left eye and jaw will never not be obvious, but the ragged flaps that had been his right nostril and the sliced-open cleft of his upper lip were basically no longer detectable. I’m not sure what that surgeon did, or how it’s even possible at all, but Wyatt simply looked like himself.

“Can I hug you?” I asked him, not sure of his pain level overall and definitely not wanting to make a wrong move. He put his arms around me instead, and the words that came out of my mouth are the absolute truth—I told him he’s beautiful.

Astonishingly enough, Wyatt had already summoned the resolve to head back into the field that very morning, the general opener of turkey season. Not deep into the woods and not to hunt himself, just onto a friend’s property to tag along, and to try to call in a bird for his buddy. He’s always been an absolute hard-charger for the outdoors, with relentless patience in a deer stand or turkey blind, literally from before his teens. But to get back in the saddle like this, so soon after an experience that could have justifiably made him a shut-in forever? I frankly don’t know how to explain it, except to note the quiet courage it must have taken to keep walking forward, into that same natural world that forged his character to begin with.

He went out again a few days later with his dad, who taught him to call birds in the first place. Wyatt took a big spring tom—not with a gun, but with his bow. For the uninitiated, this is no easy trick, perhaps the equivalent of bowling a strike with a basketball. When I congratulated him, he did what he always has and downplayed it, simply telling me it was nice to get one.

As my family can now tell you, tragedy happens. And as we’re all finding, life still has to go on, even under different terms. Aaron’s no longer comfortable camping in a tent, or simply rolling the trash can down his driveway without a twelve-gauge in hand. Wyatt no longer takes his afternoon run down the same rural roads he used to. People I’ve known for years have started to carry pepper spray to walk to the mailbox. But nobody’s packing up and heading for the city—they still have lives they love, in places they love, adjacent to the wild regions they know. They want their kids to grow up in a place that isn’t characterized by concrete and asphalt and virtual reality. They just don’t want them to die in the process.

I was with Aaron and Stacy the first time they entered Taylen’s bedroom, two weeks after the attack, to gather some of his things to send off with him when his body was cremated. Turkey feathers, fishing lures, tokens he’d saved from his one young romance. Guitar picks—I haven’t mentioned it previously, but he was an almost supernaturally gifted guitarist. Maybe that’s how he won the girl in the first place.

We’re all haunted now by two things—the loss of possibility for what should have been Taylen’s life, and whatever it was he had to endure in those violent seconds at the end of his life. No one in the family was allowed to view his body afterward, not for last respects, not for general principle, not even for identification purposes, like you see in the movies. Maybe because Taylen wasn’t even identifiable at that point. I don’t know.

I do know this: the deputies who were first on the scene the day of the attack, the ones who initially tended to Wyatt’s injuries, and then walked up on that cat in the brush and used gunfire, to get it away from Taylen? They both had brothers, too. And the first thing they did, when they got away from that harrowing scene, was call their brothers, to tell them how much they love them.

The mountain lion is indeed a majestic animal. But a majestic human being died in the prime of his life, from a broken neck and a crushed windpipe and a severed jugular, and his brother goes forward with his own scars from the same ordeal, physically and no doubt psychologically. It is my sincere hope that we can learn from what happened to Taylen and to Wyatt, and to my family by extension, and an entire community beyond that, and make the necessary adjustments to how we coexist with other apex creatures, before anything like this happens again.

Time will tell.

Note: On September 1, 2024, a five-year-old boy was attacked and mauled by a sub-adult mountain lion in a crowded picnic area at Malibu Creek State Park, near Los Angeles. The boy survived with severe lacerations to his head, after his father and others fought the lion off. Since 2020, this brings the number of attacks in California to ten.

My heart is heavy right now. I am so very sorry for the loss of your beloved Taylen. I admire the passion and deep commitment you're demonstrating as you write about this. I know you will continue to do whatever it takes to seek a living resolution for both the people we care about and the wildlife we share our lives with. Growing up in the same gold rush country in the 1970s and now living in Montana makes this feel very personal to me. You have done exceptional reporting, research, and writing. I just wish you didn't have to address this situation at all.