I killed my first deer in the Sierra foothills of northern California, one of the landmark moments of my still-young life, somewhat akin to Ralphie Parker opening up his iconic Red Ryder BB gun on that fateful Christmas morning.

Like the kid in the holiday classic, I had a wild imagination fueled by adventure stories and their archetypal heroes—in Ralph’s (slightly younger) case, Little Orphan Annie, and of course the eponymous range ridin’, rifle-totin’, comic-strip cowboy. In mine, the frontiersmen and trappers of Louis L’Amour novels, and Teddy Roosevelt’s African Game Trails.

By my sophomore year of high school I’d been downright obsessed with hunting and backwoods lore since I could remember. I was fortunate enough to live in a rural part of the California Gold Country with a dad who—not unlike the Old Man in the movie—had no compunction about setting me up with the tool of the trade and sending me out the back door to figure it out on my own. And while Ralphie in the movie just barely avoids shooting his eye out, I wound up shooting my first buck.

So here is where our ongoing story really begins—how to serve up the results. For all his estimable skills otherwise, my dad could barely make a piece of toast, and my mother had not grown up in a hunting family. More to the point, that era in the culture broadly preceded the now-renewed interest in wild foods and the hands-on acquisition of such. Words like “locavore” and “Paleo-diet” were literally decades in the future—along with the Internet, which nowadays makes a ridiculously simple task of adapting a recipe for beef into one for venison.

That left books, the old go-to medium for this boy in the first place. However—this era also preceded foodie mania in general, which meant the renaissance that produced today’s color-plated, glossy-paged embarrassment of cookbook riches was also a few years out.

My mom owned exactly one comprehensive tome, the ubiquitous Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook, which I believe she received as a wedding present. No mention of wild game at all. Meanwhile Placerville, the nearest town of any size, had two bookstores, one a dizzying maze of used offerings with little in the way of organization, and the other an esoteric New Age deal that maybe had something on lentils or tofu. And me? I may have had a hunting license, but not a driver’s license. So my mom, no doubt as uncertain as I was, took it upon herself to drive me down out of the foothills and into Sacramento, forty miles west.

We wound up in a B. Dalton’s or Walden Books, one of the now-vanished shopping mall destinations. We came up with nothing obvious at first glance, none of the classic titles I would later encounter like The L.L. Bean Fish and Game Cookbook, and certainly nothing cutting-edge like we have today from Hank Shaw or the MeatEater franchise.

What we did find turned out to be exactly right, in ways I didn’t fully understand at the time—James Beard’s American Cookery, an 800-page doorstop of a compendium, dense with minuscule font and without a single photograph. It was the store’s only offering that mentioned wild game at all, and in a dedicated chapter, no less.

I’d never heard of James Beard, as ridiculous as that sounds today. My mom of course knew who he was, her own teenage years having coincided with the high point of his fame as what would eventually be known as a “celebrity chef.” I learned much later that Beard had died within a year or so prior to that fateful day in the shopping mall, which may well be why his re-printed magnum opus was on hand in the first place. Originally published in 1972, it’s hard to imagine it otherwise would have been on a chain bookstore’s shelf in a Sacramento shopping mall nearly fifteen years later. Whatever the case, the book went home with us.

I immediately put it to use. Not only on the yields of that first deer, but because of the author’s witty, almost anthropological approach to his melting-pot thesis, simply as really good reading. Beard not only provided straight-ahead recipes in this massive undertaking, covering everything from shellfish to Hawaiian teriyaki to election cakes to—yep—squirrel, he also gift-wrapped his subjects in context, a lot of it, citing innumerable cookbooks from the Colonial era and beyond, and ruminating on the dizzying interplay of the various ethnic cuisines that descended and collided and otherwise intermarried in the early American free-for-all.

In some ways he was admirably democratic in his approach, writing about camp cooks and untrained but competent roadside diner slingers as though they were Escoffier himself. In other ways, from the current vantage, he had what could be considered blind spots—little mention, for example, of the traditional foods of the country’s original inhabitants, or the massive influence on regional cuisine from south of the border.

Then again, he was born in 1903, and claimed as his earliest memory—as a two-year-old!—a demonstration of how shredded wheat was manufactured at the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition, in his hometown of Portland, Oregon.

Seventeen years after that first formative recollection, he was expelled from Portland’s Reed College as a freshman, for same-sex liaisons. Imagine the risk, and the resulting humiliation, in that era. But instead of slinking away into permanent obscurity, he made his way to France, and spent five years immersing himself in a food culture that informed his sensibilities—and also his future success, as the original champion of sophisticated eating in American popular culture.

So like anyone in all of human history, Beard was in part a product of his own formative era—blind spots, triumphs, and all.

And in his case, a childhood in close proximity to the Western frontier, as well as the young adult’s deep-dive into classical French fare, left him perfectly situated to treat wild game not merely as a normal part of the larder, but an actual delicacy. It was exactly what I myself needed in that particular, pivotal moment.

Yes, I lived in a relatively rural setting, but most of the art- and academically inclined kids I hung out with regarded that as an insufferable bug rather than any kind of a feature, the old common trope of smart, small-town teenagers everywhere. While by that point I was fantasizing about being Robert Redford in Out of Africa, my peers were trying to finesse the radio dial to pick up Live 105 out of San Francisco, hungry for Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure. An interest as retrograde as hunting seemed to them laughably gauche, something the FFA goat-ropers and shop class grease-monkeys might go in for, but not the drama kids and, no doubt to my greater chagrin at the time, definitely not the cheerleading squad. But as much as anything, American Cookery made me realize it was perfectly okay to stand betwixt and between.

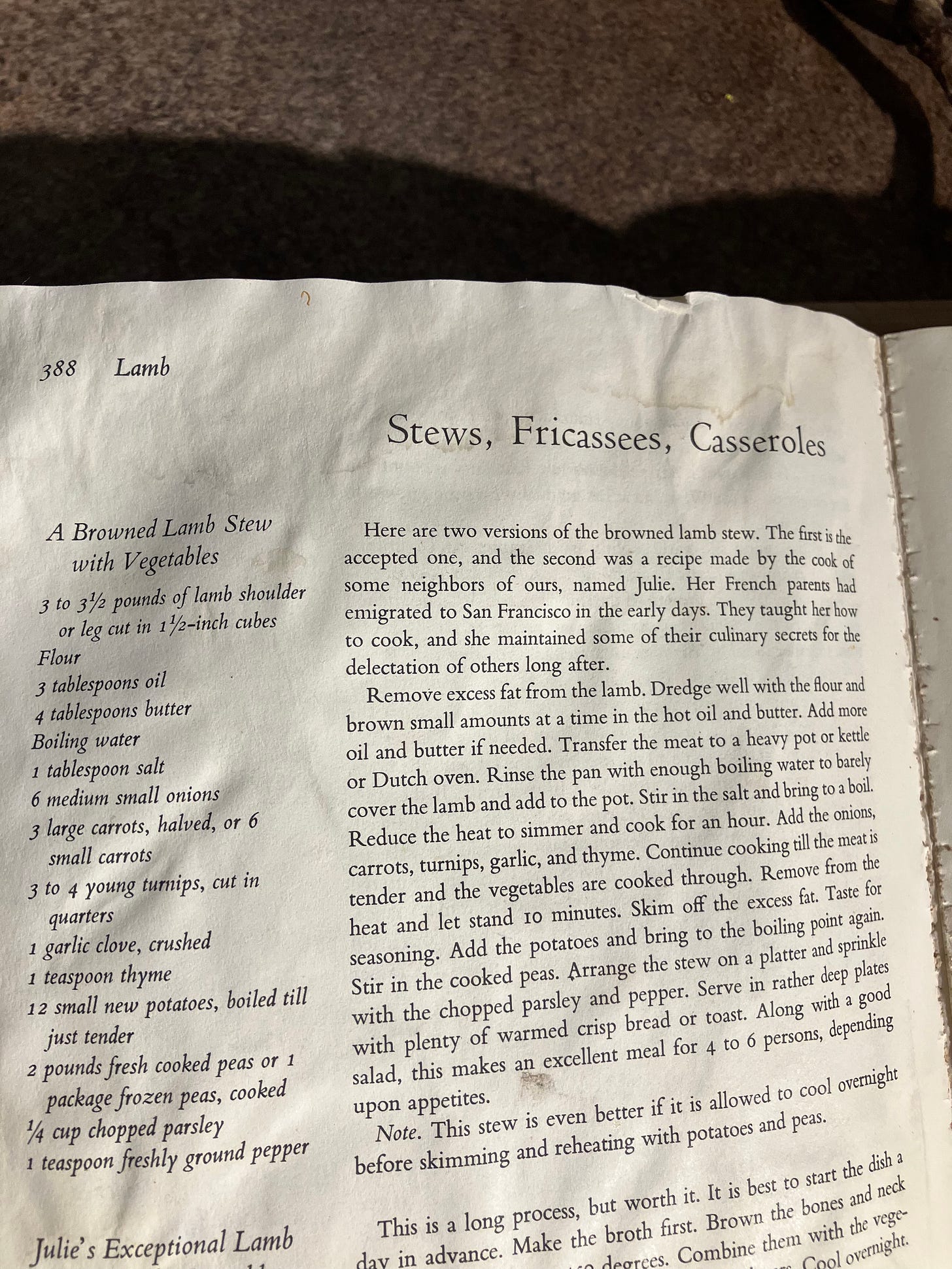

Nearly forty years on, I’m still at it, and still with the same guidebook. I tagged a Montana whitetail the day after Thanksgiving, and a few days back, my brilliant and prescient wife went straight to one of my go-to dishes, a stew I myself have probably cooked a hundred times over the years.

In a testament to Beard’s original intent, it’s not a recipe that appears under Game in the book, but a variation on his instructions for lamb, in keeping with his own observation that any number of early-day cookbooks frequently substitute mutton for venison. I’ve tweaked it further over time, cutting back on the salt and going bolder with the garlic and thyme, leaving out the turnips and peas altogether. I’ve done it with beef, once the year’s venison ran out.

It’s not complicated to make, but it never fails to jolt me back to that original wild discovery, in an urban bookstore of all places. And though my original interest in hunting was ignited by archetypal frontiersmen, in the kitchen I remain in the debt of an entirely different sort of hero—an intrepid bon vivant who happened to possess extraordinary vision, along with extraordinary taste.

Cook this dish. You’ll know what I mean.

I love this Malcolm!! Especially hearing about the little book stores in Placerville and taking the drive to Sacramento. Probably over by the Sunrise Mall!! I wonder if that mall is still there!! I haven't lived in Northern California in a long time, but this just brought back some good memories. Thank you 😊