This past week, I pulled a couple of pheasants out of the freezer and cooked a personal go-to dish for this particular bird, one I’ve made dozens of times over the last fifteen years—pheasant with horseradish cream.

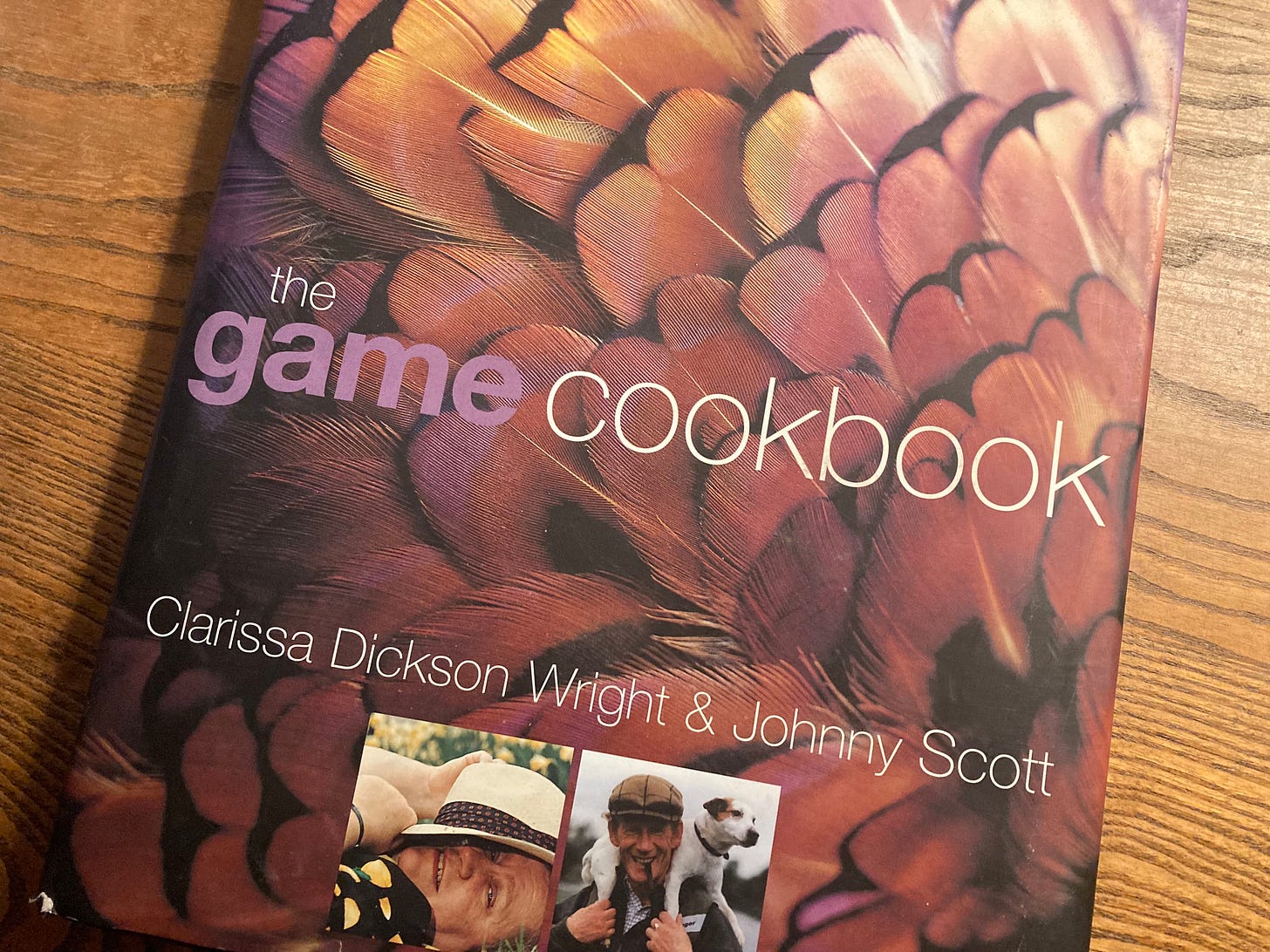

I got this recipe from The Game Cookbook, a very charming, very pretty, and very British compendium by Clarissa Dickson Wright, who was probably most famous for a cooking show on the BBC called, with hilarious candor, Two Fat Ladies, Ms. Wright of course being one of them. She and her partner-in-crime, Jennifer Patterson, tooled around the countryside on a motorcycle equipped with a sidecar—Clarissa in a WWI-style leather aviator’s helmet—exploring various aspects of traditional English cooking, including game.

At any rate, I used to hunt a lot, before life got in the way, and I’ve been lucky enough to have a series of pretty good dogs that kept me in game birds—pheasants in particular, probably a couple of dozen a season for more than a decade. So I had plenty of opportunity to try different things, sauces and techniques, but time and again, particularly if I was introducing a friend to wild game, I found myself circling back to this one unique preparation.

However—when I pulled those birds out of the freezer last week, I hadn’t cooked this dish, or eaten any pheasant at all, in more than two years. In fact, one of these birds had been in the freezer for that entire duration, tightly vacuum-sealed, occupying its own special shelf. I was aware of it, every time I opened that freezer door, knowing eventually I’d have to give in and prepare it, and also knowing exactly which dish it was destined for. But it took awhile to work myself up to the cause, because this happened to be the last pheasant I shot over the most naturally gifted bird dog I’ve had the honor to partner with, exactly one week before he died on me in the field.

For that matter, he was actually born on the couch in my living room eleven years earlier, so to say we went way back would if anything be an understatement. He was a tri-color French Brittany, black with white and tan ticking. We named him Hubert, with the appropriate Gallic pronunciation, after Saint Hubertus, the patron saint of hunters. Whether by mystical inspiration or simple chance, it turned out to be the right handle, because in the field at least, he turned out to be quite the powerhouse. We called him Bear, for short.

According to lore, French Brittanies were developed as poacher’s dogs in feudal France, when hunting was both the sport and the exclusive privilege of landed gentry, and the “noble game” very much belonged to the noble landowner. Brittanies are small by hunting dog standards—typically about thirty pounds—supposedly to make it easier for the non-nobleman to cram his canine cohort into a sack and take off running when the need arose. By the same token, they were bred to be general-duty workmates, able to point upland birds, retrieve waterfowl in a marsh, and track and retrieve furred game over hill and dale. If Bear’s array of skills are any indication, there’s some truth to the lore.

He was also, it must be noted, quite a sloth around the house. Maybe a poacher by lineage, but a loafer by inclination. If we weren’t actively stomping around on either a hunt or an off-season hike, Bear was pretty much just lolling about, perfectly content to sprawl on the floor or sleep in the sun. But the second he saw that dog whistle around my neck, he was up and at the door, ready to go, and go hard—an off-the-couch athlete if ever one existed.

A few anecdotes, in memoriam:

—Bear at a year-and-a-half, still a neophyte, but about to start shining. We were on a piece of public land outside Bridger, Montana, on a relatively warm November day. A rooster broke unexpectedly out of a Russian olive along the river and I swung the gun and shot it on pure instinct—out over the water. Bear did not see the bird come down, and in any case had never gone into the drink after actual game, and I couldn’t cajole him into understanding the situation in the moment. As the bird floated along in the current, I finally scrambled out of boots and socks, got my Carhartt’s above my knees and started wading, fully expecting to hit broken glass or rusty pipe or a snagged treble hook at any moment. I made it unscathed most of the way to the drifting pheasant when Bear cruised by with the ease of an otter, got his chops around the bird, and swam back to shore. He was a reliable water retriever from that moment on.

—A blindingly cold day outside Fairfield, Montana, maybe a couple of years later, hunting in eighteen inches of fresh frozen powder. Bear went into a small thatch of cattails ahead of me, thumped around for a moment, and emerged with a live cock pheasant in his maw. He pulled the same stunt a few more times over the years—never a hen, always a rooster. Could be chance, or maybe he could actually read the bird regulations, who knows.

—Ethan, my youngest son, jumped a handful of mallards off a stock pond and knocked one down, crippled but not dead. The duck did what they always do in that situation, and dove under water. Bear literally dove in after it, headfirst off the impoundment, fully submerged for maybe three seconds. Somehow, when he broke through the surface again, the duck was in his mouth.

—The last pheasant I killed over him, in the Jocko Valley north of Missoula, in fact within a few hundred yards of where Jocko Finley himself had his trapping camp set up in the winter of 1809-10 (don’t look for the signs, because there aren’t any). Opening day, 2022. We worked up a narrow drainage, through clumps of snowberries and wild roses. Bear veered up onto the hillside to the north, clearly working, clearly smelling something on the air as it drifted down the draw. He locked on point at a cluster of junipers, a split second before four birds roared out, three hens and a bruiser of a cackling rooster. I whiffed completely with the first barrel, connected hard with the second. Bear brought that last bird back…

A week later, a couple of miles away, hunting farther up the same creek, Bear got onto a running rooster in tall grass and wound up trailing it beyond a property boundary—maybe he could read the regs relative to roosters and hens, but true to ancestry, he was no respecter of No Hunting signs. My older boy Cole and I waited at the fence line until the bird finally flushed out ahead, and then waited for him to return. Curiously, a prairie falcon circled above him, at times only feet overhead, all the way back.

We took him to the creekbottom for a drink, then split up to hunt back to the truck. I set off with Chief, Bear’s litter mate, and Cole took Bear—only when we reconnected, Bear was nowhere to be found. Cole had lost track of him in the brush and assumed he’d hooked up with me on the other side of the water, not an unusual situation. We whistled for him, we called for him, and finally, we went out looking for him—a very unusual situation, which in and of itself did not bode well.

Long story short. A couple of hours passed before we spotted him, crumpled in the shade of a wild rose. We yelled for him, and he kicked one hind leg in the air, and we started to run, and it seemed that once he knew we were coming, he went into all-out convulsions. We got to him, and sleep got to him, in right about the same moment. And we couldn’t wake him back up.

He was eleven, so certainly no bird-of-the-year himself, but he’d never had health issues, and despite the couch potato tendencies around the house, he still got plenty of exercise. It wasn’t hot that day, and we were never far from the creek and its steady supply of water. My best guess is that he simply had a heart attack, doing what he loved to do, on that last long trespassing run beyond the fence line. I’d like to think the falcon circling above him knew something we didn’t, in the moment, and carried part of him along.

I carried the rest of him to the truck. We buried him behind the house the next morning, situated to give him his own long view from the bluff. I didn’t hunt anymore that year, nor very much of the next, either—2023 stands as the first year since the ‘90s that I failed to take a single rooster.

This past fall, though, marked a return. We got out again like we meant it, had a wonderful pheasant opener, and before long had another half-dozen roosters in the freezer, alongside that one memorial bird. And I knew it was past time to bring Bear’s last game full circle, to honor both the bird and the dog in the best possible way.

Bear may not have come from royal stock, but it was a meal fit for a king. Try it yourself, and you’ll know what I mean.

A pair of short films made by my compadre Nick Davis, in conjunction with the State of Montana, capturing Bear in his hard-charging prime…rabbits and chukars and grouse, oh my…

The only thing bird dogs do that break your heart is when they finally go. This was a beautiful piece Malcom.

What a beautiful piece of writing and such a moving tribute to 'Bear'. He sounds like a wonderful being. That falcon probably did know a few things....